What you will learn:

•R-134a refrigerant will be phasing out

•The reasons why R134a has been difficult to obtain

•What to expect in the future of mobile air climate control refrigerants

By now you’ve probably heard that something is going on with the supply of 30-lb. refrigerant cylinders. We sure have, as the MACS office has taken many calls from members across North America. They want to know why their local stores have run out of products to sell, and (probably just as important) why the price per cylinder has more than doubled in just a few short weeks. We started getting these "supply and price" calls back in mid-November.

We don’t know why this is happening in every situation; some could be caused by regional market demands, usage fluctuations due to changing weather patterns, or even the supply chain disruptions that we keep hearing about on the national news. But we have a pretty good idea that two major EPA rules may be part of the underlying story.

We'll explain each of these in more detail coming up, but for now, let's dispense with the suspense. First, there's the national phasedown of HFCs, and second is the ban on disposable cylinders. (Figure 1).

The phasedown is probably the more immediate reason for the current supply shortage and subsequent price increases since step one (a 10 percent economy-wide reduction in the consumption of HFCs which includes an entity-specific allowance program) took effect on Oct. 1, 2021 (which was the start of the US Federal Government's 2022 fiscal year).

The ban on disposable cylinders is likely also a factor, but probably not so much right now since it won't fully be in effect until 2027. We'll get into that more in a bit, but for now, let's see how we got here in the first place.

EPA’S HFC Phasedown has begun

On Dec. 27, 2020, President Trump signed into law the Consolidated Appropriations Act (aka the Second COVID-19 Stimulus Relief Bill), which at $2.3 trillion is one of the largest spending bills in U.S. history. (Figure 2). It combines $600 billion in COVID relief with $1.4 trillion in twelve different appropriations bills. One of them is the AIM Act.

Building is a complex of several historic buildings in the Federal Triangle in Washington, D.C. The Environmental Protection Agency is headquartered here. Credit: Steve Schaeber

AIM stands for the American Innovation and Manufacturing Act, which establishes three main types of regulatory programs for EPA:

1) The economy-wide phasedown of the production and consumption of listed HFCs (hydrofluorocarbons)

2) The transition to next-generation technologies by sector

3) The management of listed HFCs. For automotive service shops and technicians, this means R-134a

After years of back-and-forth court battles over the EPA's 2015 and 2016 HFC regulations (which they lost in the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals), the AIM Act has finally given the EPA the statutory authority they need to regulate HFCs (like R-134a) in the same way that they regulate ODS (ozone-depleting substances) like R-12.

Note: The AIM Act is a law that was written by and voted on by members of the U.S. Congress (both the House of Representatives and the Senate), and then signed by then President Donald Trump. This means that the authority which the AIM Act gives to the EPA is statutory. It’s a law that can only be changed through another act of Congress.

There are certain provisions of AIM which are similar to Title 6 of the Clean Air Act (one of which is Section 609), but there are clear differences between the two. The AIM Act is a separate authority for the EPA, and it includes a state preemption clause that overrides certain existing state laws.

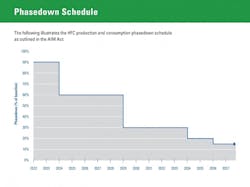

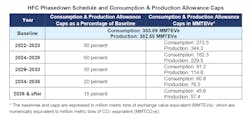

For the refrigerant phasedown, the EPA had a deadline of Sep. 23, 2021, to issue a final rule on an allocation program. Then, by Oct. 1st of each year (which is the day that the federal government's fiscal year begins), they will allocate HFC allowances for the following year. AIM specifies a phasedown calculation (based on 2011-2013 production and consumption of HFCs), which starts with a 10 percent reduction in 2022 and increases to 85 percent by 2036 (Figure 3).

What is the phasedown schedule?

The EPA has established production and consumption baselines using the formulas in the AIM Act. They allowed production and consumption levels will decrease relative to the baselines, consistent with the schedule established in the Act. The following table provides the consumption and production limits (Figure 4).

Technology transition

In transitioning to new technologies, the EPA has been authorized to restrict the use of HFCs on a sector-by-sector basis. While nothing is in the works right now, it is possible that the EPA could restrict the use of R-134a in motor vehicle air conditioning (MVAC) (similar to their failed rule for 2021 model year vehicles), which would help facilitate our industry’s transition to R-1234yf. It’s unclear whether or not this will happen (since by our calculations about 85 percent of new vehicles being manufactured today already use yf), but they have the authority to do that, should they choose.

Either way, we don’t think that the EPA would restrict the use of R-134a for servicing the existing vehicle fleet, considering that retrofitting to R-1234yf is already not allowed. Plus, as time goes on and older vehicles are retired (and thus replaced by ones that use yf), there will simply be fewer vehicles that require R-134a for service. This in itself will reduce demand for and use of this HFC.

This is similar to what happened with R-12 vehicles back in the day. The first R-134a cars hit the Dallas streets in 1991 (Ford was first in the US with the 1991 Ford Taurus, and Dallas-Fort Worth was their test market), and the last with R-12 was the 1995 Jeep Wrangler (YJ). The ensuing years had shops using both refrigerants, including a lot of retrofit work. But by about 2010, most of the R-12 work was already gone. Even some specialty shops we spoke with recently said they have worked on just a few R-12 cars over the past few years.

So, if we rough out the timeline, 1991 to 2010 is 19 years. The first yf car was the 2013 Cadillac XTS (launched in 2012), and we still don't have our last R-134a vehicle (Mazda and Mercedes are the last two holdouts here in the US). 2012 plus 19 years is 2031. This means we can figure on about 10 more years of working with R-134a while it dwindles. During the same time, we'll be using R-1234yf a lot more.

HFC management

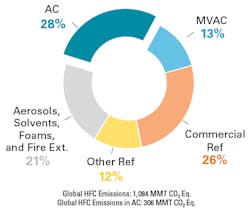

As for the management of HFCs, this speaks to another regulation that was shot down by the courts, focusing mainly on calculating and repairing leaks on commercial refrigeration (like those giant A/C systems and refrigerators at the big box stores). Of course, there's always a possibility that MVAC could be included in their program. MVAC is the third-largest source, accounting for 13 percent of global HFC emissions (Figure 5).

A grant program for purchasing R/R/R machines?

Probably of most interest to shop owners, is that AIM provides for a targeted small business technology grant, for the purchase of approved refrigerant recycling equipment. This is the only place in the 2,124-page law that specifically calls out, "the service or repair of motor vehicle air conditioning systems". The program hasn't yet been put together, and it is subject to appropriations, but it does provide for limited matching funds of $5,000,000 for each of the fiscal years 2021 through 2023. So, keep this in mind if you have an R-1234yf machine that you've been thinking about!

Note: To date, there have not been any appropriations made for this grant program (there have been no monies applied towards it), and the EPA has not yet set up the program. But we’ll let you know when they do.

R-134a price and supply

So, back to the main questions: What’s going on with the price of R-134a? Why is there a (perceived) shortage of R-134a supply?

Last summer, we expected only to see a modest increase in price at this point, considering that the new regulations call for only a 10 percent reduction for 2022 thru 2024. We are just as surprised as you are to have seen such a sharp increase! We also didn’t expect to see shortages of this magnitude. Sure, there could be regional issues, but we’re hearing of outright sales stoppages across the country.

One member in Florida said their supplier (a large national retail auto parts distributor) had completely discontinued sales of 30-pound cylinders of R-134a in central Florida because their main warehouse in Orlando had none in stock (as of Dec. 20, 2021). Another MACS member (one who sells refrigerant) said that while they normally stock cylinders for resale, they have also discontinued sales because their supply has been cut off.

A member in Vancouver, British Columbia (Canada) told MACS that their shop is currently restricted to purchasing only one cylinder at a time (and at a 50 percent markup on the September price).

Still another MACS member in North Carolina said they were first allowed to buy two cylinders per day from their distributor, but later in the week, they were cut down to only one cylinder per week. His exact words were, "...one per week, heck. I need one cylinder each day!"

In California, a member commented that their price had tripled, and going back to Florida, another member said he cannot get refrigerant from any of his suppliers. His comment was, “...even if I could get any, they want to charge me more than double of what I just paid in November!”

We checked on eBay and found cylinders for sale between $275 and $340 (as of Dec. 23, 2021) which increased to $430 and $450 (as of Jan. 7, 2022) and came back down to $382 (as of Feb. 16, 2022).

We also checked Amazon, but no cylinders were being offered for sale. This may be due to the recent EPA warning about small cans being sold on the site, which were being offered for sale as “Cool Penguin F-12” and contained illegal chemical blends, including some that deplete the ozone layer.

Phasedown background

The goal of the AIM Act’s phasedown is to reduce HFC use by 85 percent over the next 15 years, which lines up the United States with provisions of the Kigali Amendment to the Montreal Protocol.

The Montreal Protocol is an international treaty that gradually eliminates the production and consumption of ozone-depleting substances (like R-12), which was signed by the US in 1987 and ratified in 1988. As a result, the US stopped manufacturing and importing R-12 by 1995. This is how we came to use R-134a in mobile A/C systems in the first place.

The Kigali Amendment to the Montreal Protocol does the same thing for HFCs (like R-134a), but with a slightly longer time horizon. The US signed onto Kigali back in 2016 (basically agreeing to what is written in the document), but it has not yet been ratified, which means we are not yet legally bound by it. President Biden has directed the State Department to seek "the advice and consent" of Congress over ratification, but to date, we have no progress updates. Ratification may soon be just a formality, however, since EPA's proposed new rule follows the Kigali plan anyway.

So, what does all this have to do with refrigerant prices? That’s what technicians and shop owners want to know. Many of you remember what happened in the mid-90s during the R-12 transition to 134a. A 30-pound bottle of R-12 that used to cost around $26 quickly rose to $300 or so, which was followed by several years of price volatility. Then we had regional supply issues to deal with, partly due to stockpiling and hoarding (there are still people today who swear that 30-pound bottle they bought in 1996 is worth over $1,000). The EPA has set up a website where you can read the full text of their plan. Here's a link: https://www.epa.gov/climate-hfcs-reduction

The big can ban

Yep, you read it right. There’s a “big can ban” on the way for those 30-lb disposable cylinders that EPA just wrote a rule about, although it’s still a few years out. Even so, we figure it has something to do with the recent supply shortage and price increases.

Part of the AIM Act requires the EPA to issue regulations that phase down the production and consumption of regulated substances (R-134a in our case). This is where we get the 10 percent reduction for 2022 and the new allocation program. But the EPA says it also has the responsibility to make sure that this phasedown occurs, and they are concerned that people will try to get around their regulations and import HFCs illegally into the United States.

To help make sure this doesn’t happen, the EPA will prohibit importing or filling disposable cylinders in the US beginning on Jan. 1, 2025 (Figure 6). They will also prohibit the sale and distribution of disposable cylinders beginning Jan. 1, 2027. Instead, EPA will require the use of refillable cylinders.

Also known as DOT-39 cylinders (because of the DOT regulation they’re required to meet), these are the 30-lb cylinders that we’ve been using in repair shops for decades. Shops typically buy these cylinders (new and pre-filled with refrigerant) as needed, maybe keeping one or two extra in stock, just in case; And then put them on their scrap pile for recycling when empty.

Some look at this as a waste, since they are one-time use cylinders. Instead, why not reuse them? The DOT-39 cylinder is strictly not allowed to be refilled for safety reasons. To ensure this, they have a one-way valve. However, in other parts of the world, reusable cylinders are the norm. They have a heavier-duty construction and can be refilled with specialized equipment.

When the new regulations take effect, shops instead will (probably) rent a cylinder from their supplier, who will fill it with refrigerant as needed, likely through a cylinder exchange program. This would be similar to how shops currently work with other refillable cylinders (for example, oxygen and acetylene for their torch, argon for their MIG welder, or nitrogen for pressure testing and system purging).

The EPA considers this ban on disposable cylinders to be a strong component of their enforcement and compliance tools that will deter illegal activity in the HFC market. Studies in Europe (which has had F-gas rules in place for many years, including the banned use of R-134a in new vehicles since 2017) have shown that 10 million tons of illegal F-gas were imported in a single year. This was done through open and traditional smuggling.

By requiring the use of refillable cylinders, the EPA says it can better enforce compliance through administrative consequences and increased oversight on imports. They will also establish an ID tracking system using QR codes to track the movement of HFCs. They also intend to work with CBP (U.S. Customs and Border Protection) to establish an automated system that will track an importer's allowances in real-time.

Of course, EPA’s regulation has not gone through without a hitch. Several industry groups have begun legal proceedings to challenge these new rules in court, but they’ve only just begun, and we’ll have to wait a while to see how they turn out. So, while 2027 may seem far off, planning (and the lawsuits) has begun now, and so an effect is sure to be felt in the marketplace.

The small can ban

On May 17, 2021, Governor Jay Inslee of Washington signed House Bill 1050 into law, which regulates HFCs (hydrofluorocarbons) at the state level. Most of the new law has to do with non-mobile sources of HFC emissions. Residential and commercial air conditioning (like the central A/C systems in homes and offices), vending machines, and those large refrigerators and freezers at the big box grocery stores. It also regulates small appliances (mini fridge), foam blowing agents, chillers, and cold storage warehouses. But the one section that applies to mobile A/C does what the heading suggests: bans the sale of those small cans of R-134a refrigerant (Figure 7). Here’s what it says:

"No person may sell, offer for sale, or purchase any of the following: A regulated refrigerant in a container designed for consumer recharge of a motor vehicle air conditioning system or consumer appliance during repair or service."

This part of the law has already taken effect on July 25, 2021, but it seems that word has not yet reached all the stores. A MACS survey found that small cans are still being offered for sale. We called five auto parts stores across the state (Seattle, Spokane, Tacoma, Vancouver, and Yakima) and asked if they had small cans of refrigerant for sale. Three stores said they did have cans on their retail shelves. Another said they are running low on stock, and don't know if they'll be getting any more. Only one store said they heard about the ban.

So, at this point, we expect small cans will continue to be available in WA until word gets around (since it will just take time for everyone to learn about and implement the new rule), but soon they will not be available in the auto parts stores.

Please note that WA’s law specifically allows the purchase of small cans for recharging off-highway construction and agricultural equipment. So, you should still be able to buy small cans of R-134a at the farm store. Also, the law only affects the sale of HFCs, and not HFOs, so small cans of R-1234yf will still be sold across the state (Figure 8).

Washington is not alone in adopting new HFC laws. Following the back-and-forth court cases about EPA’s rules #20 and #21, California was the first state to do so which made up for them at the state level. Washington was second but is the only one, so far, to address small cans. Several other states have enacted or are considering new HFC bills too, including Colorado, New Jersey, Oregon, Vermont, Virginia, and others. And now that the EPA has their HFC authority (thanks to the AIM Act of 2020), we expect things to slow down somewhat, on the state level. But this is not where it stops for small cans.

Part of the AIM Act says that people can petition the EPA to write new rules that restrict the use of regulated substances (HFCs like R-134a) in a regulated sector. So far EPA has received more than ten such petitions, but only one relates to MVAC. It’s from IGSD (the Institute for Governance and Sustainable Development), and they’ve asked EPA to consider replication of Washington House Bill 1050’s common-sense restrictions on consumer containers containing high global warming potential HFCs. If EPA decides to do this, it will likely take a year or so before we start seeing small cans removed from store shelves nationwide. Now we have to wait for the EPA to act. It has been considering IGSD’s petition (along with several others) over the past few months, and we expect to hear something about it soon. Here’s a link to find Washington’s HB1050: https://app.leg.wa.gov/billinfo/

Comments and questions

MACS receives a lot of great feedback from readers (both here in Motor Age magazine and ACtion magazine), and we thank you all for that! There's a lot to keep up with, and we try to do our best to cover the issues in full and in-depth. But as things go, sometimes answers lead to more questions, and so, we'll address a few of the latest comments we received.

One reader said that he thought self-sealing cans were supposed to replace those un-valved cans from store shelves years ago, yet he sees they are still being sold at some of the big box stores. We looked into this ourselves and checked a few stores local to MACS, and sure enough, some of the cans didn't have a self-sealing valve. The reason is that the EPA set a date of Jan. 1, 2018, for manufacturers to switch over to using self-sealing cans, however, they did not restrict the sale of old stock. There were no date codes on the cans we saw, but it's likely that warehouse distributors and retail outlets still have pre-2018 small cans left over, and they're going to try and sell them out.

Another comment had to do with "Unlicensed Joe" being able to buy small cans of refrigerant, and it's true: there are no restrictions on the sale of small cans of R-134a or R-1234yf (except in Washington State, which recently banned all consumer recharge cans of R-134a). This has been an ongoing challenge in the industry and is a balancing act between the consumers' right to repair their property and the regulatory burden placed on the professionals. With the introduction of the AIM Act, there is still a possibility that consumer access to small cans could be restricted in the future but there is no federal-level action at the moment.

Someone else asked if there is a limit on the number of small cans that can be purchased in a single transaction, and the answer is “no.” A consumer is allowed to purchase one, two, ten, or even one hundred small cans of refrigerant at a time (Figure 8). The EPA did not limit purchase amounts by volume (except to say that individual cans must be two pounds or less) when they wrote the original small can rule back in 2016, and in fact, they addressed a similar comment in their 2021 rulemaking, saying, "...purchase limits... are outside the scope of the proposal."

We also learned a little more from the feedback about what's behind the recent price and supply issues with 30lb cylinders of R-134a, which we want to further explore in this article. Of course, there's always more going on behind the scenes than we can figure on, and so with a little digging, this is what we've heard.

On a high level, the AIM Act is surely the driving force behind the market disruption, but we have to remember that the act doesn't just affect mobile A/C. It covers all HFCs, in all uses, in all sectors of the US economy. It's because of this, that we are seeing issues.

EPA's phasedown program works to reduce HFC consumption by allocating certain amounts of HFCs (refrigerant 134a, in our case) to each of the major manufacturers, blenders, wholesalers, and retailers (think companies like Arkema, AutoZone, Chemours, Honeywell, Koura, National Refrigerants, Walmart and the like). Then, each company must decide how they are going to use their allocations. This depends on the products that they make, and the submarkets into which they are sold.

Here's how it works

The EPA allows companies to bring a certain amount of GWP-equivalent (Global Warming Potential) HFCs to market each year, on a declining scale beginning this year in 2022. Companies of course are in the business of making products at a profitable price, so it stands to reason that if they can make one product at a higher profit margin than another, then that's what they are going to do.

For example, let's take a look at "Company A" which makes two well-known, widely used refrigerant products, R-134a (for automotive use) and R-410A (commonly used in residential HVAC). R-134a is itself an HFC regulated by the EPA, while R-410A is not specifically regulated; rather it is a blend of two other regulated refrigerants: R-32 (50 percent) and R-125 (50 percent).

If "Company A" has 100 credits to use in 2022 (and next year will only have 90 credits), they can choose to make either R-134a at a profitable margin or combine R-32 and R-125 to make R-410A at a better profit (or they can make some of each). In this scenario, it depends on which market has the higher supply/demand/margin scenario at the time (automotive or residential). But it’s not just about how they’re going to use their allocation to make R-134a, it’s how they’re going to divide up their allocation to make all other HFCs, at a profit, while keeping in mind that their allocation is going to drop in future years. I just want to add one more thing: EPA does allow companies to trade their credits, which adds yet another layer of complexity.

So, in our scenario, there is no shortage of R-134a in and of itself; it's just not as available because of the higher price. Company A has decided that the residential market is very large and will pay the higher price for R-410A. They may still make some R-134a, but because it's not as profitable in the marketplace, they're going to raise the price.

As for our commenters who couldn't find R-134a, we think some of that has to do with the increased price. In other words, it's not that they couldn't get it, just that they couldn't get it at 2021's price. Part of this may be the retailers, who may not have ordered before the phasedown took effect. Or maybe they didn't order after the phasedown, thinking the price is going to come back down. Then some hoarded R-134a by purchasing in bulk, anticipating the supply/demand scenario to begin, and restricted supply to the market while they waited for the price to climb.

So, while "Parts Store A" may have plenty to sell at a certain price, "Parts Store B" may not have much in stock, and so their price is much higher. There's enough availability, you just have to find the right source for it (at the price you're willing to pay). Over time we expect these issues to continue, particularly as allocations are reduced.

We also heard from a commenter who asked, "Does this mean we won't be able to get R-134a anymore? Are they going to stop making it?" The answer of course is “no,” and although right now it's somewhat harder to find (especially at last year's price), there are plenty of refrigerants available. But it looks like the price is going to be much higher than it was.

Fluctuations like this are nothing new to the refrigerant market. We've seen price increases and supply shortages for more than 30 years (we've seen the price drop, too!). Much the same thing happens at the gas pumps. Today I can buy gas in Lansdale, Pennsylvania, for $3.79 per gallon when it cost just $2.29 a year ago.

Who knows what it will cost next year!