Powerstroke Engine Choked Under Pressure

I was contacted by a brilliant friend of mine named Brent (owner of Advanced Diagnostic Consulting in Washington State) regarding a 2005 6.0L Powerstroke diesel engine exhibiting a misfire. Like any experienced diagnostician Brent began with the easy-to-grab information. His relative compression test results quickly pointed him to suspect cylinder No. 4 was not performing the same as the other seven cylinders.

Easy testing lead to pinpointed analysis

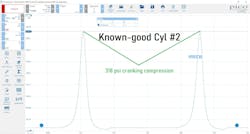

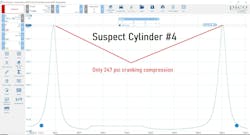

Convinced he was experiencing the results of an engine mechanical fault, Brent moved to capture compression waveforms with a WPS 500 pressure transducer and digital storage oscilloscope from Pico Technologies (Figure 1). An in-cylinder cranking compression waveform was captured for the suspect cylinder No. 4 and a known-good cylinder No. 2 (from the same bank) for comparison. The known-good cylinder yielded a healthy 318 psi compression tower (Figure 2). However, the suspect cylinder’s compression was significantly lower.

Not only was the compression lower in suspect cylinder No. 4, but the shape of the cranking waveform presented similar to a running-waveform from a gasoline internal combustion engine (with a throttle plate) (Figure 3). At this point he reached out to me for some input.

After analyzing the data and comparing the captures to each other it’s clear that the fault is limited to a single cylinder. The two deductions I made were:

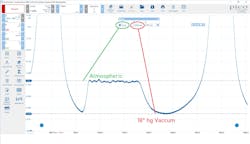

- The low compression had nothing to do with a leak (as indicated by the even exhaust and intake pockets, marked with the lower horizontal cursor) (Figure 4).

- The cylinder cannot inhale. This is evident by the induction stroke creating the rounded (pocket of 18” hg vacuum) as the piston descends and tries to draw air to fill the cylinder.

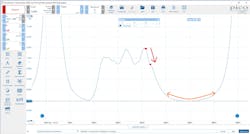

I then had Brent capture a running in-cylinder compression waveform for the suspect cylinder No. 4 (Figure 5). After looking closely at the capture, the change in pressure indicated by the red arrow points to the opening of the cylinder’s intake valve. However, the rounded pocket indicated air can’t get past the valve opening. I reached out to Brent with my findings, and I inquired about the clearance of the intake valves. Brent removed the valve cover and verified not only were the clearances proper, but then Brent witnessed them open with the valve cover removed. The question becomes: “Why can’t the cylinder inhale?”

The data doesn’t lie

With all the information in front of us, and the desired information not yet obtained, we are faced with deciding how to proceed. Here are some bullet points of what we know to be factual, and I will ask all of you, diligent readers, for your input:

- Only Cylinder No. 4 has low compression.

- Cylinder No. 4 seals properly, has no leaks.

- The intake valves operate properly and clearances are adjusted correctly.

- Cylinder No. 4 cannot inhale.

Given this information, what would you do next?

- Inspect for inlet restriction specific to only cylinder No. 4.

- Inspect camshaft for intake lobe damage/wear.

- Verify cam timing.

- Replace restricted air filter.

About the Author

Brandon Steckler

Technical Editor | Motor Age

Brandon began his career in Northampton County Community College in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, where he was a student of GM’s Automotive Service Educational program. In 2001, he graduated top of his class and earned the GM Leadership award for his efforts. He later began working as a technician at a Saturn dealership in Reading, Pennsylvania, where he quickly attained Master Technician status. He later transitioned to working with Hondas, where he aggressively worked to attain another Master Technician status.

Always having a passion for a full understanding of system/component functionality, he rapidly earned a reputation for deciphering strange failures at an efficient pace and became known as an information specialist among the staff and peers at the dealership. In search of new challenges, he transitioned away from the dealership and to the independent world, where he specialized in diagnostics and driveability.

Today, he is an instructor with both Carquest Technical Institute and Worldpac Training Institute. Along with beta testing for Automotive Test Solutions, he develops curriculum/submits case studies for educational purposes. Through Steckler Automotive Technical Services, LLC., Brandon also provides telephone and live technical support, as well as private training, for technicians all across the world.

Brandon holds ASE certifications A1-A9 as well as C1 (Service Consultant). He is certified as an Advanced Level Specialist in L1 (Advanced Engine Performance), L2 (Advanced Diesel Engine Performance), L3 (Hybrid/EV Specialist), L4 (ADAS) and xEV-Level 2 (Technician electrical safety).

He contributes weekly to Facebook automotive chat groups, has authored several books and classes, and truly enjoys traveling across the globe to help other technicians attain a level of understanding that will serve them well throughout their careers.